Category: Huntington's Disease

Objective: We aim to analyze the main epidemiological characteristics of individuals having a Huntington disease phenotype in Eastern Algeria population.

Background: Huntington’s disease (HD) is the most frequent autosomal dominant chorea in the world, it is caused by an abnormal and unstable repeat expansion of CAG triplets in the HTT gene [1]. HD usually manifests in the adulthood by chorea, cognitive, psychiatric and behavioral impairments chorea [2]–[4]. There is no prior clinical or epidemiological study of HD or of other hereditary chorea in the Algerian population limiting the patients access to care.

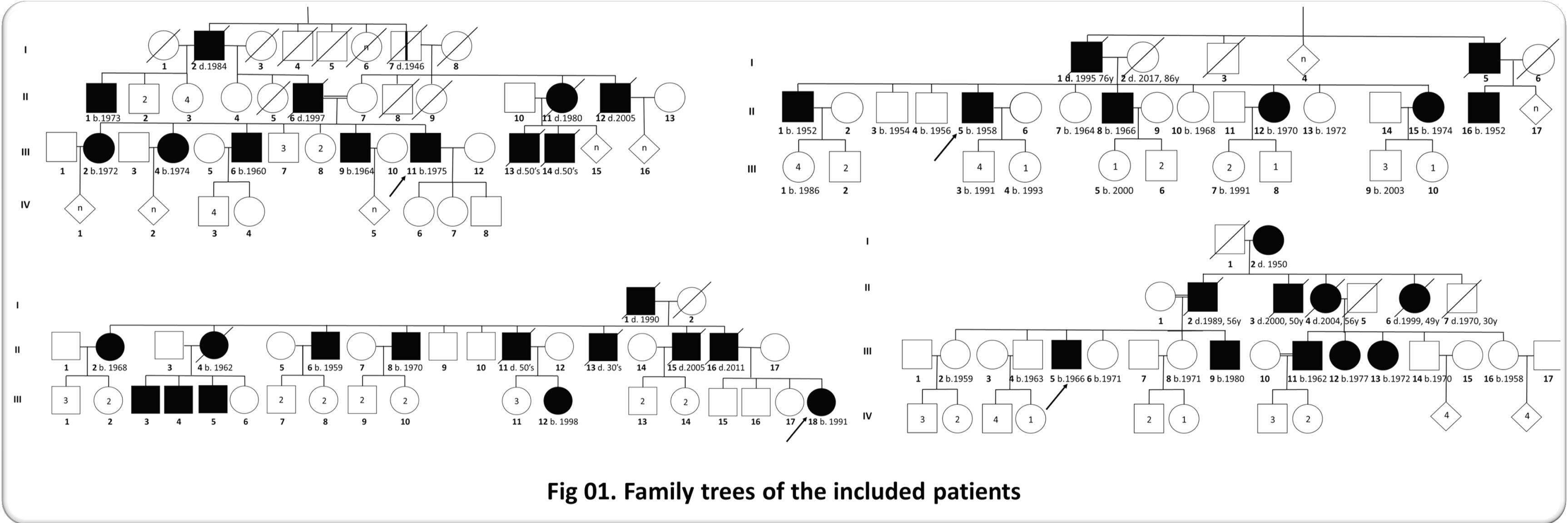

Method: We performed a cross-sectional and retrospective analysis of the epidemiological data collected between 2015 and 2022 in Benbadis Constantine University Hospital. We included 45 symptomatic patients from 4 families originating from Eastern Algeria and having a HD phenotype without the presence of signs suggesting other etiologies.

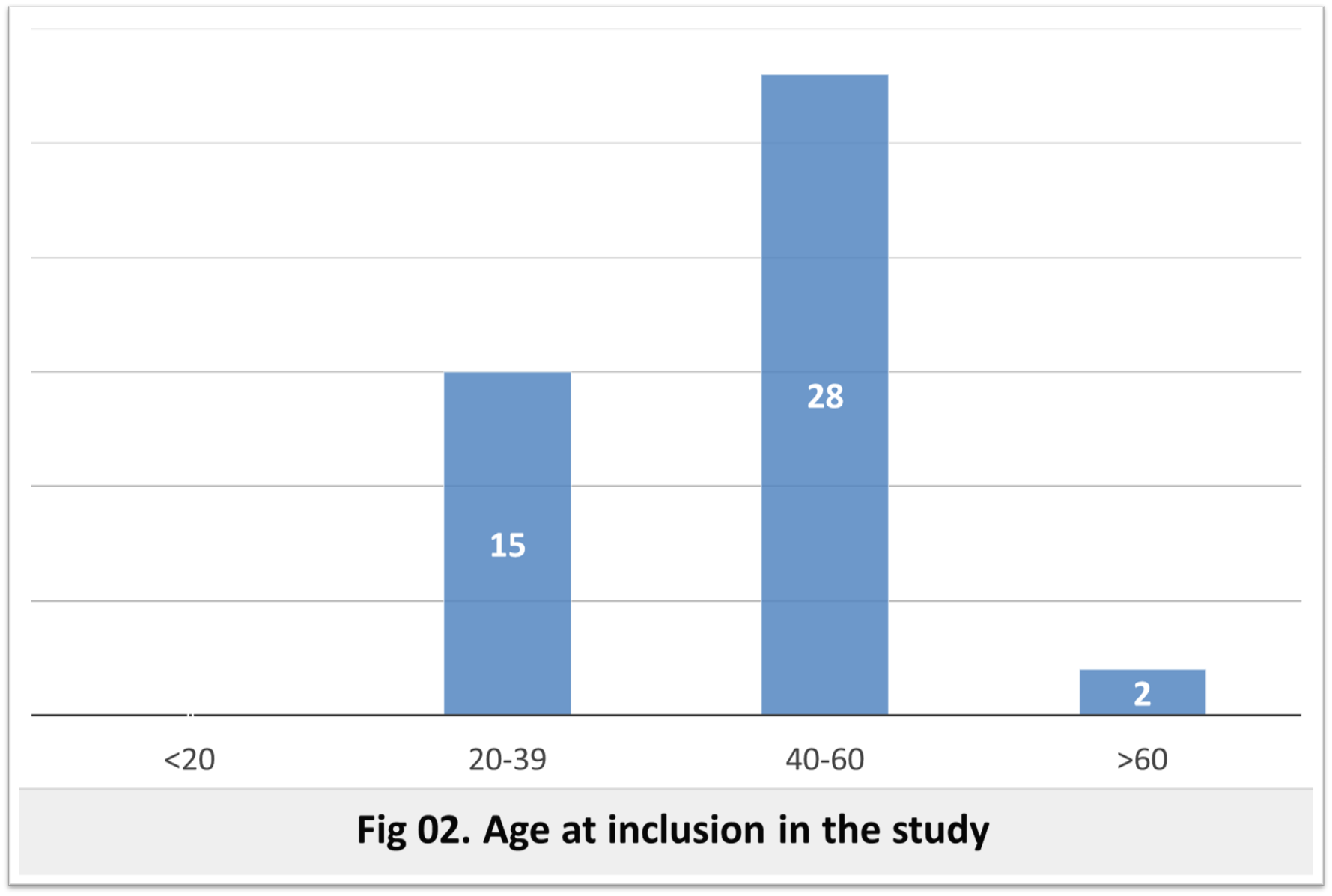

Results: The frequency was 1.25 per 100 000 inhabitants lower than the world average frequency (2.7 per 100,000 inhabitants [5] which can be explained, as in the other African cohorts, by poor access to care [6]. The sex ratio was 2.21, whereas it is 1 in the literature, which may be explained by a fear of social stigmatization of affected women. At the time of inclusion 25 patients are alive with an average age of 49.6 years (23-69 years), the most represented age group is between 40-60 years. The age of motor onset was variable between 21 and 71 years, it is between 40 and 60 years in 62.22% of cases and between 20 and 40 years in a third of cases. This intergenerational variability is related to anticipation phenomena with paternal transmission [7]. The inter-familial variability is probably related to a different number of CAG repeats and/or the effect of different genetic modifiers [8]–[11]. The mean age of death was 56.42 years and is similar to literature data [12]. Genetic testing is needed to confirm the HD diagnosis or of other HD phenocopies (HLD2, C9orf72….).

Conclusion: More efforts need to be made to collect more information, include more families and perform genetic analysis of patients and suspected cases. The goal is to create a national cohort including all the epidemiological, genetic and clinical data of the Algerian population and to establish local management recommendations.

References: [1] M. Macdonald, “A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes,” Cell, vol. 72, no. 6, pp. 971–983, Mar. 1993, doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-E.

[2] C. A. Ross et al., “Huntington disease: natural history, biomarkers and prospects for therapeutics,” Nat. Rev. Neurol., vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 204–216, Apr. 2014, doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.24.

[3] E. R. Dorsey et al., “Natural history of Huntington disease,” JAMA Neurol., vol. 70, no. 12, pp. 1520–1530, Dec. 2013, doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.4408.

[4] A. Barbeau, R. C. Duvoisin, F. Gerstenbrand, J. P. Lakke, C. D. Marsden, and G. Stern, “Classification of extrapyramidal disorders. Proposal for an international classification and glossary of terms,” J. Neurol. Sci., vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 311–327, Aug. 1981, doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(81)90109-x.

[5] M. D. Rawlins et al., “The Prevalence of Huntington’s Disease,” Neuroepidemiology, vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 144–153, 2016, doi: 10.1159/000443738.

[6] M. R. Hayden, J. M. MacGregor, and P. H. Beighton, “The prevalence of Huntington’s chorea in South Africa,” South Afr. Med. J. Suid-Afr. Tydskr. Vir Geneeskd., vol. 58, no. 5, pp. 193–196, Aug. 1980.

[7] N. G. Ranen et al., “Anticipation and instability of IT-15 (CAG)n repeats in parent-offspring pairs with Huntington disease,” Am. J. Hum. Genet., vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 593–602, Sep. 1995.

[8] J.-M. Lee et al., “Identification of Genetic Factors that Modify Clinical Onset of Huntington’s Disease,” Cell, vol. 162, no. 3, pp. 516–526, Jul. 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.003.

[9] M. Ciosi et al., “A genetic association study of glutamine-encoding DNA sequence structures, somatic CAG expansion, and DNA repair gene variants, with Huntington disease clinical outcomes,” EBioMedicine, vol. 48, pp. 568–580, Oct. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.09.020.

[10] G. E. B. Wright et al., “Length of Uninterrupted CAG, Independent of Polyglutamine Size, Results in Increased Somatic Instability, Hastening Onset of Huntington Disease,” Am. J. Hum. Genet., vol. 104, no. 6, pp. 1116–1126, Jun. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.04.007.

[11] D. J. H. Moss et al., “Identification of genetic variants associated with Huntington’s disease progression: a genome-wide association study,” Lancet Neurol., vol. 16, no. 9, pp. 701–711, Sep. 2017, doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30161-8.

[12] F. B. Rodrigues et al., “Survival, Mortality, Causes and Places of Death in a European Huntington’s Disease Prospective Cohort,” Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract., vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 737–742, Oct. 2017, doi: 10.1002/mdc3.12502.

[13] R. A. C. Roos, “Huntington’s disease: a clinical review,” Orphanet J. Rare Dis., vol. 5, p. 40, Dec. 2010, doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-40.

[14] R. Ghosh and S. J. Tabrizi, “Clinical Features of Huntington’s Disease,” in Polyglutamine Disorders, vol. 1049, C. Nóbrega and L. Pereira de Almeida, Eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018, pp. 1–28. [Online]. Available: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-71779-1_1

To cite this abstract in AMA style:

Y. Mecheri, D. Satta, F. Serradj. Epidemiological analysis of autosomal dominant chorea in Eastern Algeria [abstract]. Mov Disord. 2023; 38 (suppl 1). https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/epidemiological-analysis-of-autosomal-dominant-chorea-in-eastern-algeria/. Accessed July 18, 2025.« Back to 2023 International Congress

MDS Abstracts - https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/epidemiological-analysis-of-autosomal-dominant-chorea-in-eastern-algeria/