Objective: To compare the clinical and kinematic assessment of bradykinesia (movement slowness).

Background: Bradykinesia may be present not only in Parkinson’s disease (PD), but also in essential tremor (ET) and in normal elderly subjects [1-3]. In some cases, the detection of bradykinesia by clinical examination may be challenging, and no objective cut-offs have been identified at kinematic analysis.

Method: Simultaneous video and kinematic recordings of finger tapping were performed in 44 PD patients, 69 ET patients, and 77 healthy subjects (HCs). Videos were blindly evaluated by 7 neurologists, according to standardized clinical scales. Kinematic recordings were analyzed offline by a dedicated software [3]. We calculated the inter-raters’ agreement by the Fleiss’ K. We compared clinical scores and kinematic data with ANOVAs. Clinical evaluation scores-stratified density plots were used to evaluate the overlapping in the distribution of the kinematic data. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to identify cut-offs to distinguish between subjects with bradykinesia (median clinical scores ≥ 2) and those without bradykinesia (median clinical scores < 2).

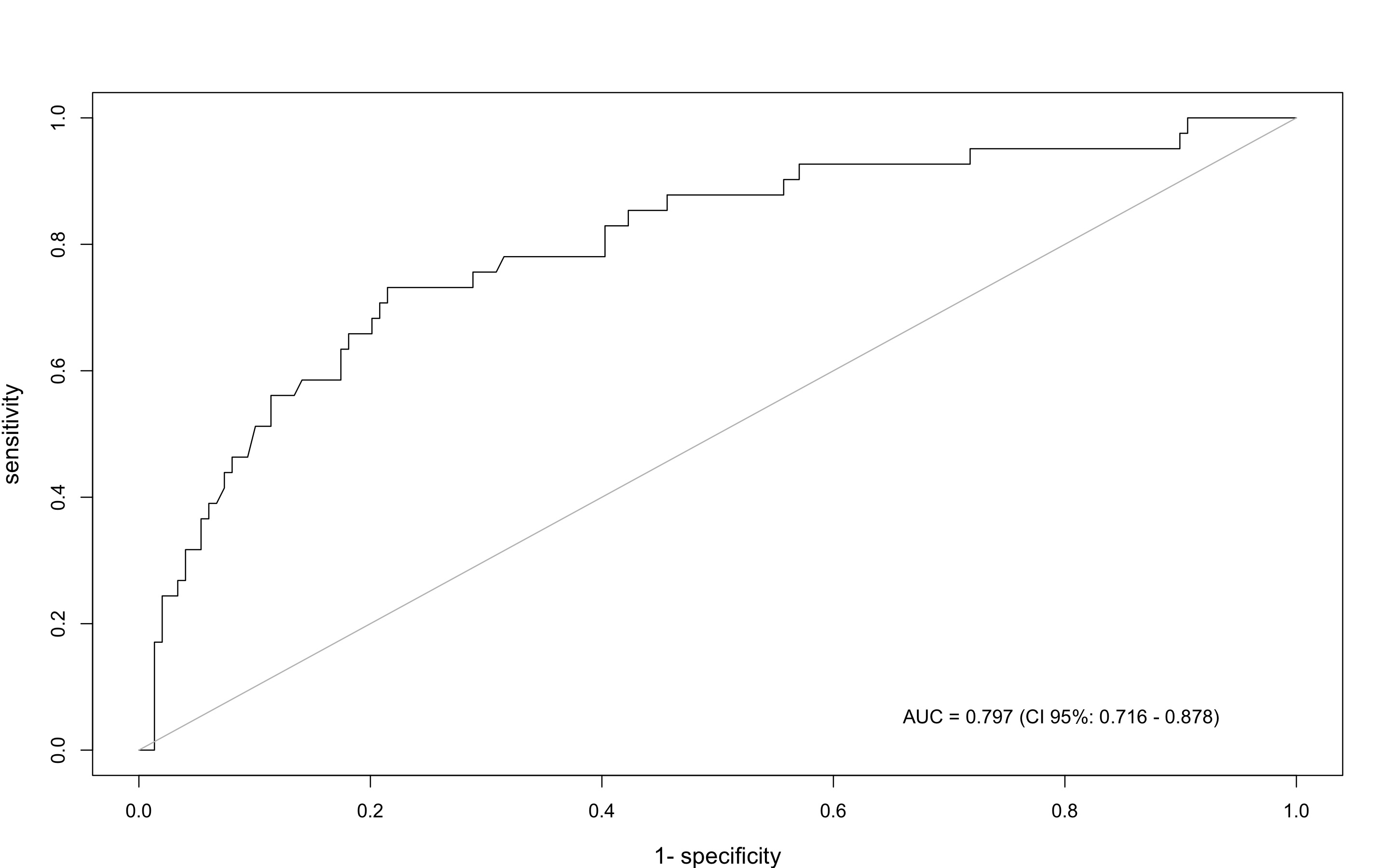

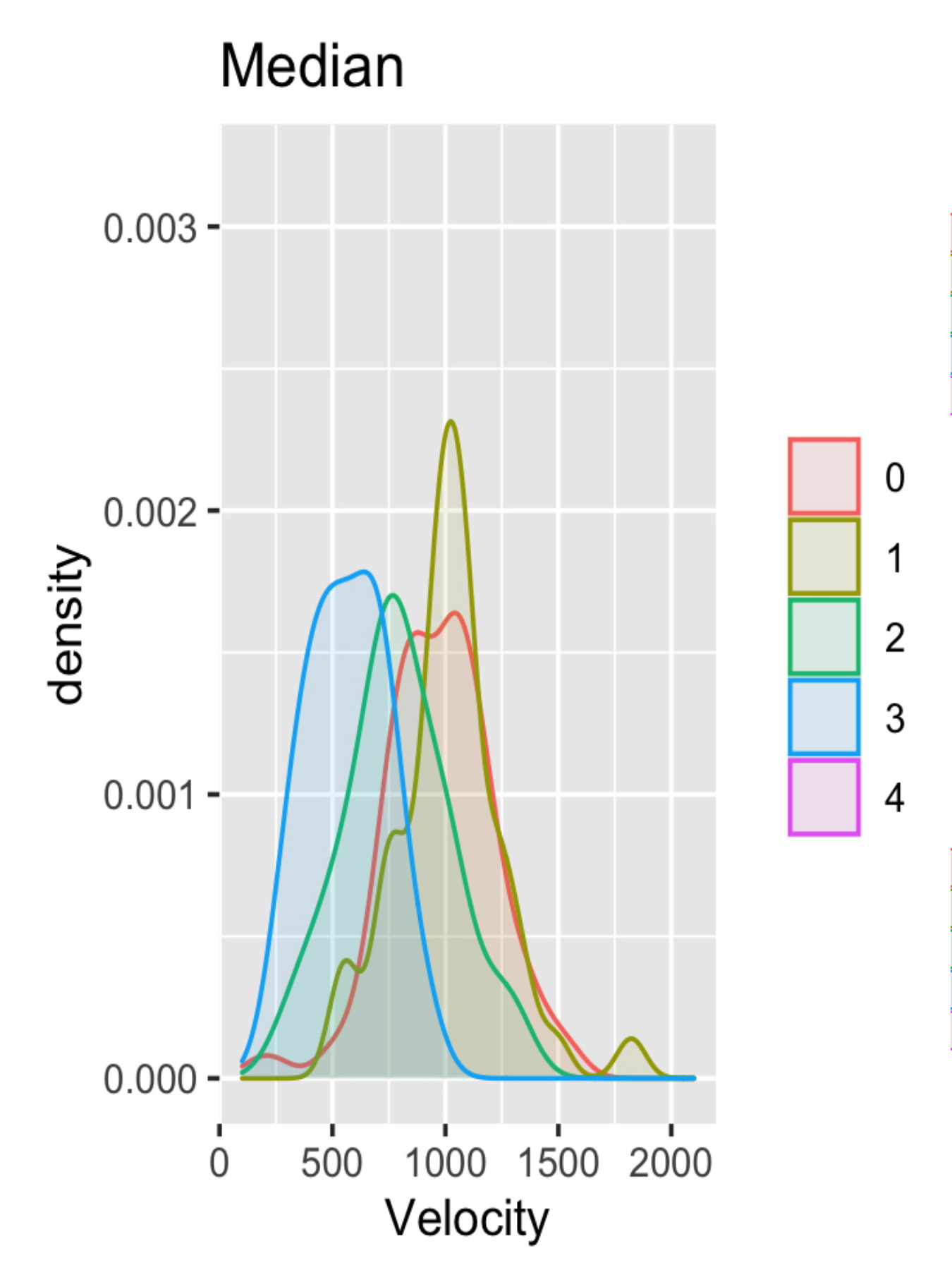

Results: We found a fair agreement among raters (Fleiss K=0.34). We found the highest clinical scores in PD, and higher scores in ET than in HCs (all p values<0.001). The kinematic analysis showed that the three groups differed in terms of movement velocity and amplitude, with the lowest values being detected in PD (all p values<0.001). Density plots demonstrated a marked overlapping between kinematic data curves, indicating that a given clinical score reflected a wide range of movement velocities [Figure 1]. ROC curves showed that kinematic distinguished subjects with and without bradykinesia (AUC=0.797, 95%CI 0.716-0.878) [Figure 2]. The kinematic cut-off of 730 degrees/sec had a sensitivity of 0.923 (95%CI 0.640-0.998) and specificity 0.847 (95%CI 0.786-0.897).

Conclusion: We here compared clinical and kinematic assessment of bradykinesia and identified a possible cut-off value distinguishing subjects with and without bradykinesia. The study results may be relevant for bradykinesia detection and patients’ classification.

References: 1. Bologna M, Paparella G, Fasano A, Hallett M, Berardelli A. Evolving concepts on bradykinesia. Brain. 2020 Mar 1;143(3):727-750. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz344. PMID: 31834375; PMCID: PMC8205506.

2. Paparella G, Fasano A, Hallett M, Berardelli A, Bologna M. Emerging concepts on bradykinesia in non-parkinsonian conditions. Eur J Neurol. 2021 Jul;28(7):2403-2422. doi: 10.1111/ene.14851. Epub 2021 May 18. PMID: 33793037.

3. Bologna M, Paparella G, Colella D, Cannavacciuolo A, Angelini L, Alunni-Fegatelli D, Guerra A, Berardelli A. Is there evidence of bradykinesia in essential tremor? Eur J Neurol. 2020 Aug;27(8):1501-1509. doi: 10.1111/ene.14312. Epub 2020 May 31. PMID: 32396976.

To cite this abstract in AMA style:

G. Paparella, A. de Biase, L. Angelini, A. Cannavacciuolo, D. Colella, A. Guerra, D. Alunni Fegatelli, A. Berardelli, M. Bologna. Comparison between clinical and kinematic assessment of bradykinesia [abstract]. Mov Disord. 2022; 37 (suppl 2). https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/comparison-between-clinical-and-kinematic-assessment-of-bradykinesia/. Accessed July 26, 2024.« Back to 2022 International Congress

MDS Abstracts - https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/comparison-between-clinical-and-kinematic-assessment-of-bradykinesia/